Why Is Africa on the Fence About Elon Musk's Starlink?

The high-speed internet technology holds the potential to bridge the digital gap in Africa, but a range of concerns has left most of the continent uneasy about Starlink.

Elon Musk might muse that it’s easier to send rockets to the Moon and Mars than to deploy his high-speed internet service across the continent—right here on Earth.

Over the telephone, the head of DR Congo’s telecommunications agency, Christian Katenge, appeared to be in a hurry and had little time for us. His straightforward and business-like manner was reflected in the concise answers he provided to our questions.

“We will listen to their proposals and understand their current and future plans,” Katenge told the African Gazette regarding Starlink. “Then we will authorise their operations, provided they comply with our regulations, ensure equipment homologation, authorise resellers, and obtain the necessary licences.”

When confronted about the perception of being a control freak, Katenge did not shy away. “Yes, it’s about control,” he said, “but it’s also about showing respect for an entire country, the Democratic Republic of Congo.”

From Cape to Casablanca, Starlink’s fortunes in its attempt to conquer the African market have been rather diverse—hard to pin down to one common factor. However, the regulatory hurdles it faces in the DRC illustrate a wider trend, as we shall discuss. But first, what exactly is Starlink?

Internet From Low Earth Orbit

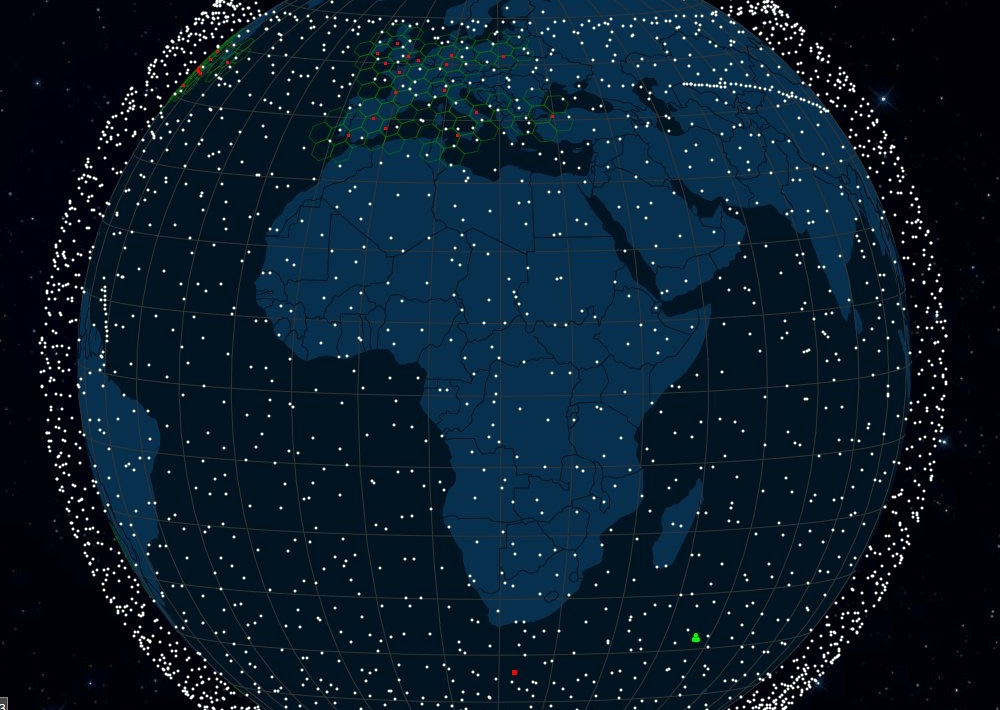

At the heart of Starlink is a network of satellites woven across the night sky, hovering above the atmosphere of our planet, mapping its curvature meticulously, leaving no point of the compass uncovered.

With his own space company, SpaceX, and that reusable Falcon 9 rocket launcher, along with a mind busy with plans for terraforming Mars someday, placing that vast network of satellites in orbit has been little more than an added thrill for Elon Musk.

Now, what’s just one small source of dopamine for the tech entrepreneur may prove to have consequential impacts across the world; Starlink comes with the revolutionary promise of reinventing high-speed Internet.

“It will be useful in that it will provide Internet in areas not covered by GSM networks, with all the benefits it brings for communication in rural areas,” Christian Katenge admits, even as his country is cautious about embracing it.

There are several reasons why the company may give you pause. As one former NASA physicist warned, the Starlink system poses a risk to life on Earth, with its potential to jeopardise the planet’s magnetic field, the very shield that protects us from deadly solar radiation.

This is more than mere tech scepticism; the issue of space debris has long been a concern, and the need to clean up low Earth orbit—just above the atmosphere—is a pressing topic in scientific circles.

But low Earth orbit pollution is not the reason Starlink has encountered obstacles on the continent, though the company seems on track to clear the hurdles up in its path.

“You’ve become so successful and you’re investing in various countries; I want you to come home and invest here.”

—Cyril Ramaphosa, to Elon Musk

Come Home, Elon

Elon Musk is not one to dwell on his origins. Some Africans who point out online that the world’s richest man was born in South Africa have occasionally fallen victim to vicious internet trolls, who offer unsolicited advice, suggesting that Africans should learn to stand on their own rather than whistle at Musk for attention and aid.

Well, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa was certainly not whistling for mere crumbs when he recently picked up the phone to speak with Elon Musk.

“You’ve become so successful and you’re investing in various countries; I want you to come home and invest here,” Ramaphosa reportedly told Musk, adding that they would have further discussions.

Was this the president sucking up to the billionaire? Not at all; Ramaphosa was seeking to resolve a rather strange paradox. How?

Starlink has now become operational in almost all the countries surrounding Musk’s native South Africa; countries like Zambia, Eswatini, Malawi.

Zimbabwe—after initial tough talk warning against any illegal operations within its borders—has now become the 14th African country to welcome the company. However, conditions in South Africa have kept Starlink at bay.

Of course, there are the usual regulatory requirements, but under South African legislation, Starlink must demonstrate local Black ownership of up to 30 percent.

This reflects the authorities’ desire to remedy historical inequalities stemming from the legacy of apartheid.

Elon Musk, however, is a champion of merit and has publicly opposed Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives and Affirmative Action.

If Starlink is to operate in South Africa, it will require an extraordinary business arrangement or a compromise on Musk’s part.

But if you will believe President Ramaphosa, discussions are underway for the native son to come home and invest.

Elsewhere across the continent, where there is no apartheid legacy to address, the hurdles facing Starlink are of a different nature.

National Security

“The concerns of the telecom agency are not clearly understood,” DR Congo’s consumer advocate John Aluku tells the African Gazette. “For Starlink, it simply needs to establish itself as a Congolese commercial company.”

“[...] The regulator cannot act as an obstacle since it will not allocate satellite frequencies to Starlink, which already has them.”

The lawyer barely contains his irritation as he dismisses the authorities’ caution as unwarranted.

“The regulator is responsible for implementing effective measures for the development of telecommunications in the DRC; it should not hinder its own objective.”

As far as Aluku is concerned, the internet is essential for the information society, and opening the door to Starlink would solve many problems.

The inadequacy of basic telecommunications infrastructure has delayed DRC’s transition to digital; and Starlink services will enhance connectivity for the Congolese population, especially those in rural and remote areas.

John Aluku is willing to make a strong case for why the country needs Starlink, but Christian Katenge—ever pragmatic—insists on his one talking point: without a title, one is not permitted to operate a telecommunications service in the DRC.

It’s an understatement. The DRC is a country brimming with natural resources, including precious minerals such as cobalt, and Silicon Valley needs the Congo to fuel its growth.

However, due to its wealth, the country has known little peace since gaining independence from Belgium.

One thorn in the side of Congolese officials is the M23 rebellion, allegedly backed by foreign countries. The DRC is at war.

Under these circumstances, officials have reason to be strict in exerting control over any telecommunications services within the country’s borders.

Of course, that’s convenient for internet censorship when the streets are in turmoil. But there’s more that officials are concerned about:

Without strict control, allowing a foreign entity like Starlink to operate could pose security risks, such as enabling espionage or cyberattacks.

News of the recent anti-immigration riots across the UK and the alleged role of Elon Musk’s X in enabling those riots adds to the anxiety in Kinshasa.

Call them control freaks, but the DRC is a traumatised country, much more vulnerable to tech abuse than the United Kingdom.

As it were, it would be simplistic to dismiss Kinshasa's attitude toward Starlink as solely driven by a desire to control information and suppress free speech.

No, the Democratic Republic of Congo has legitimate concerns over digital sovereignty and national security.

Across the continent in West Africa, where insecurity in the Sahel is a regional headache, similar national security concerns are keeping Starlink out.

The satellite service has been blocked for approval in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Mali.

Authorities across the Sahel worry that terrorist organisations may use the service to better coordinate their attacks on civilians and military targets, worsening an already bloody situation.

In contrast to the Sahel and the DRC, Starlink has been operational in neighbouring Rwanda since February 2023.

And also next door in Burundi, a presidential decree signed in May 2024 grants a licence for the company to bring its service into the country.

As it stands, Starlink has not run into hurdles everywhere, but the company has seen enough that Elon Musk might be musing that it’s easier to send rockets to the Moon and Mars than to deploy his high-speed internet service across the continent, right here on Earth.