The Enduring Legacy of Burkina Faso’s Slain Captain Thomas Sankara

Thirty-seven years after his brutal assassination, Thomas Sankara's vision resonates powerfully, inspiring a new generation of Burkinabè to reclaim their nation's sovereignty and identity.

“We had to give some sense of meaning to the revolts of the unemployed urban masses, frustrated and tired of seeing the limousines of the alienated élite flash by, following the head of State, who offered them only false solutions devised and conceived in the brains of others.”

— Thomas Sankara, UN General Assembly, 1985

The youngest serving president on the planet—Captain Ibrahim Traore of Burkina Faso—is a man in a hurry, not because of that perpetual spring in his step. No.

Two years ago, at just 34, Traore inherited a country in turmoil. Islamists, empowered by the fall of Libya, have been wreaking havoc in remote corners of the nation. Traore has a war to win, as it is. But importantly, Traore must give hope to a traumatised country where everything is urgent.

Obviously, the young president has little time to spare. And he seems to have figured out that a maximum of straight-talking would save him time, or at least avoid confusion as to what his priorities are.

To anyone familiar with African politics, especially politics in Burkina, Traore is but a reincarnation—the political heir to another captain, Thomas Sankara, who had walked in his shoes 37 years ago.

Sankara’s story is one laced with tragedy, which returns every year centre stage in the national consciousness. And on Tuesday, the straight-talking Traore was on cue with a tribute.

“Today, 15 October,” President Traore tweeted to the world, “the people of Burkina Faso remember the cowardly and ignoble assassination of President Captain Thomas Sankara.”

“I pay tribute to this great visionary who has indelibly shaped the history of our Nation with his integrity, patriotism, and unwavering commitment to a dignified, free, and sovereign Burkina Faso.”

There’s a great deal to unpack in this tribute, delivered with generosity. So, what then is the story of this great visionary, whom an entire nation feels a duty to remember forever?

A Tragic Day

Afternoon. 15 October 1987. As the squad tasked with eliminating Captain Thomas Sankara arrived at the villa of the Council of the Entente in Ouagadougou, the capital city, they felt at least assured of one thing: from the carnage they were about to unleash, there would be no survivors. They felt that they would be triumphant forever, with no soul to hold them to account.

Of course, the assassins left no note detailing their motivations. Even Alouna Traoré, the mysterious sole survivor of the massacre—whose fragile testimony offers a direct glimpse into the murderous frenzy of that day—cannot definitively describe what truly drove these men.

Yet, the scorched-earth tactic they deployed that afternoon spoke more eloquently and more credibly than any confession or direct testimony. They sought no prisoners. Despite having the option to disarm and detain their unfortunate victims, they went in for a permanent solution.

The operation lasted around thirty minutes. But the grim task was effectively over as soon as the first bursts from their AK-47s rang out. Sankara was struck twice in the forehead—fatal blows.

Half an hour later, while the shooting continued, the PF—the President of the Faso—was already dead. He had long ceased to breathe.

Among the twelve fatalities who shared Sankara’s tragic lot were four civilian members of an ad hoc cabinet convened to address a specific matter of policy. Their names are known: Paulin Bamouni, Patrice Zagré, Frédéric Kiemdé, and Bonaventure Compaoré.

The other unfortunate victims were military personnel from the revolutionary army, serving as bodyguards or drivers for the presidential convoy. Among them was Adjutant Christophe Saba—the proverbial figure of the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. Saba was off duty. He had merely swung by for a chat among chums.

As you can see, 15 October 1987 as it unfolded in Burkina Faso was no fiction. And the thirty-seven years that have passed since have done nothing to diminish the brutality of what transpired that day.

But if Captain Thomas Sankara has grown even more popular in death, it is not solely due to his tragic end.

An Upright Man

Thomas Sankara was a man haunted by the destitution of the masses in the former French colony of Upper Volta, where he grew up in relative prosperity.

He never went hungry, and was fortunate to receive an education. This was because his father—Joseph Sankara—was a gendarme, who belonged to the small elite.

Shielded from the pervasive poverty around him, Thomas nonetheless wondered: how is it that some can eat to their fill while others all but starve? And it was a question that would never leave him alone, even after he assumed power on 4 August 1983.

“We had to take the lead of the peasant uprisings in the countryside, threatened by desertification, exhausted by hunger and thirst, and abandoned,” he told the UN General Assembly in 1984, as he outlined the vision of his popular revolution.

“We had to give some sense of meaning to the revolts of the unemployed urban masses, frustrated and tired of seeing the limousines of the alienated élite flash by, following the head of State, who offered them only false solutions devised and conceived in the brains of others.”

To deliver on this highly promissory rhetoric, Sankara knew he had to walk the talk—he wouldn’t be one of the alienated ones rolling in a limo. He drastically reviewed the lifestyle of government employees, starting from the top.

He awarded himself a meagre monthly pay of $450, refusing to use the air conditioning in his office, which he considered a luxury. The Captain sold off two-thirds of the government’s auto fleet and made the Renault 5—the cheapest car sold in Burkina Faso at that time—the official service car for ministers.

In a great departure from tradition, the captain rejected nepotism and turned away relatives who sought sponsored jobs, abusively leveraging their personal connections.

And there was no favours for mom and dad. Thomas’s parents continued to live in their old modest house in the popular neighbourhood of Paspanga, where they’d pass away in near-destitution decades years after their son’s assassination.

On the first anniversary of his revolution, Sankara decided to discard the colonial name, Upper Volta, given to his country. He swapped it with Burkina Faso, the Land of Upright People.

Burkina Faso was a programmatic name; it subconsciously urged every citizen to honesty, to integrity. And Sankara—a believer in leadership by example—was the ultimate upright man, the ultimate Burkinabè. The Captain couldn’t afford to skimp on that value. Why?

Integrity was the spiritual essence necessary for advancing the urgent public policies needed to lift millions out of poverty and to cement Sankara’s legacy as a transformative figure.

“We want to democratise our society, to open up our minds to a universe of collective responsibility, so that we may be bold enough to invent the future. We want to change the administration and reconstruct it with a different kind of civil servant.”

—Thomas Sankara, October 1984

A Man In A Hurry

“We refuse simple survival,” Thomas Sankara vowed in his UN speech, recycling ideas familiar to even his most remote observers. “We want to ease the pressures, to free our countryside from medieval stagnation or regression.”

“We want to democratise our society, to open up our minds to a universe of collective responsibility, so that we may be bold enough to invent the future. We want to change the administration and reconstruct it with a different kind of civil servant.”

“We want to get our army involved with the people in productive work and remind it constantly that—without patriotic training—a soldier is only a criminal in waiting. That is our political programme.”

As he addressed the world diplomats, Sankara had only been in power for a year. He was, in fact, presenting the roadmap for his presidency, which was to last for just four short years.

To meet his ambitious vision, the young revolutionary leader needed policies aimed at radical reforms. These spanned various sectors. And they led to significant changes, with lasting impact.

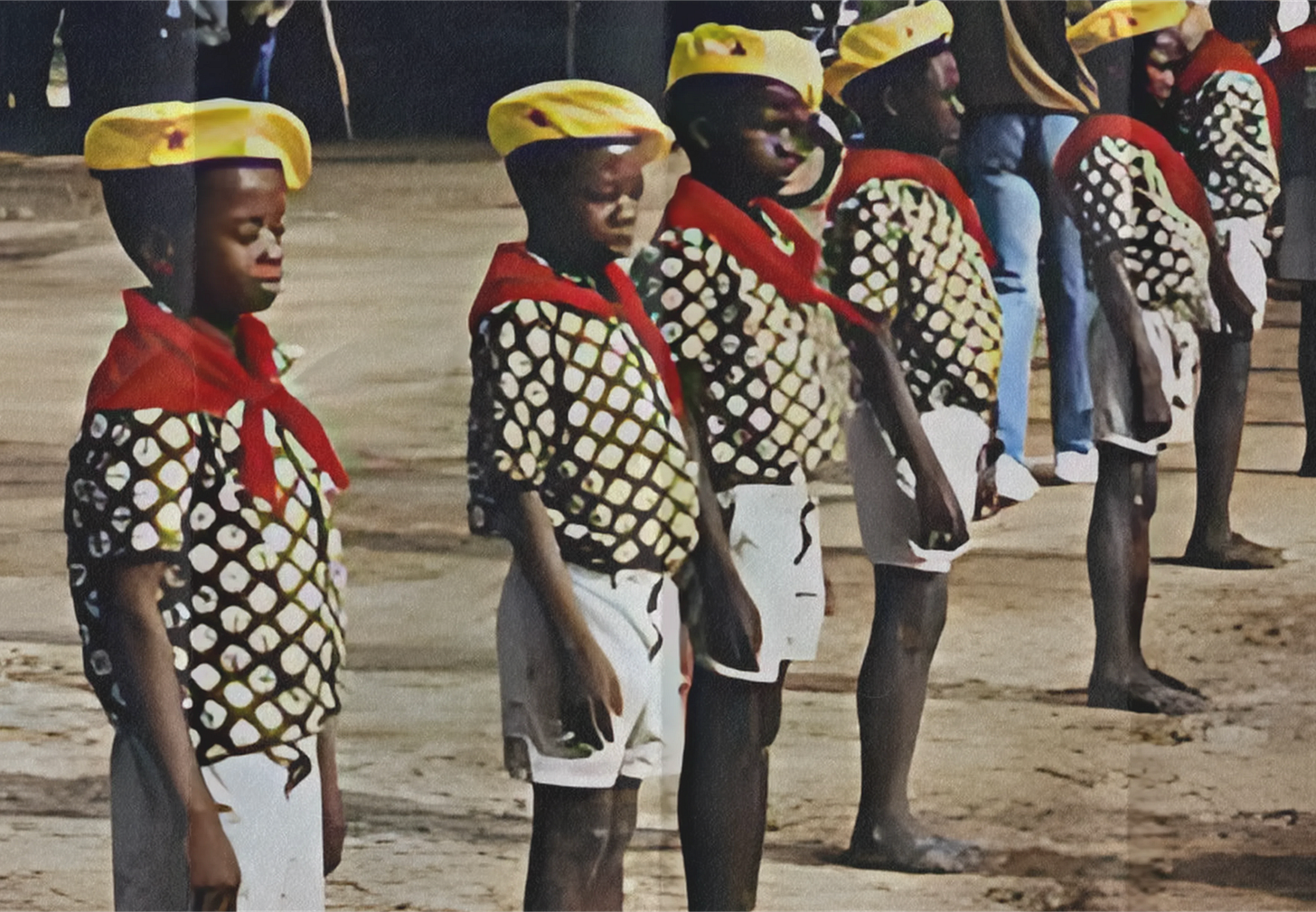

Sankara introduced free education at all levels, focusing on accessibility for all children, particularly in rural areas, which significantly increased literacy rates in the country.

Beyond maths and literacy, the revolutionary school system placed emphasis on civic education. The goal was to instil early in the youth a sense of national identity and responsibility.

The curriculum ensured that every Burkinabè child was sharply aware of the importance of self-sufficiency and social justice. And as important alongside education to the revolutionary project was women’s liberation. Why?

Upper Volta was a conservative country of the West African type. Certain entrenched beliefs in gender roles left women at a disadvantage. It was a situation that Sankara had to address, as part of his pledge to break his country free from medieval stagnation.

At the horror of traditional chieftaincies that were deep-rooted in their old ways, the government moved to champion women’s rights, promoting gender equality as a core principle of public policies.

Sankara appointed women to prominent government positions and encouraged their participation in politics and employment. But his gender reforms were far more reaching, as he implemented programs that prohibited forced marriages and encouraged family planning.

The Captain famously said, “The revolution cannot succeed without the emancipation of women.” And while women’s rights were a crucial part of his agenda, the young leader also prioritised the protection of the environment.

As a matter of fact—long before global warming became a pressing issue—Thomas Sankara, whose country sat on the edge of the Sahel, had an acute awareness of the importance of environmental conservation.

He launched massive tree-planting campaigns to combat desertification and improve agricultural productivity. This included the famous Green March—La Marche Verte—aiming to restore degraded land.

Every school across the country was driven under the One School One Grove initiative—Une Ecole, Un Bosquet—to keep schoolchildren planting trees as a core part of their education.

The revolutionary green policies advocated for agricultural practices that were environmentally friendly. They aimed at achieving food security, while promoting organic farming techniques.

“Our economic ambition is to work to ensure that the use of the mind and the strength of each inhabitant of Burkina Faso will produce what is necessary to provide two meals a day and drinking-water,” Sankara declared.

In line with this stated goal, Sankara’s government promoted policies aimed at reducing dependency on foreign aid and imports. Consommons Burkinabè—or Let’s consume what we produce—was one familiar slogan to the people of Burkina Faso under the Revolution. And it was more than a catchphrase.

In real life, it translated into support for local industries and agriculture to boost self-sufficiency. And produce made in Faso was distributed through the Faso Yaar open market chain across cities.

Sankara didn’t care about Bretton Woods economic prescriptions. His policies were informed by African customs of solidarity. In the village of his parents—as in all villages across the country—value is not systematically measured in market terms. Certain things have no price.

So, as part of his efforts to place the destiny of the nation in the hands of all, Sankara nationalised several sectors, including mining and transport, redirecting profits to social programmes and infrastructure development.

And for the management of public companies, he demanded complete transparency, and there was a price to pay for dishonesty—a price decided by a revolutionary jury of one’s peers.

At any rate, he went full force against corruption through strict regulations and accountability measures for public officials. As noted earlier, he famously reduced his own salary and that of his ministers.

And he will forever be remembered for encouraging grass-roots participation in governance, breeding a culture of honesty and popular involvement in decision-making processes.

That was Thomas Sankara at home. But his revolution wasn’t complete without a brave foreign policy; one of anti-imperialistic eloquence that concerned itself with the fate of all “the wretched” of the earth.