Rwandan Diaspora in Canada Pleads for Testimony in Federal Probe

Exiled critics of Rwandan government say they have been overlooked as Canadian authorities delved into subversive activities of foreign operatives, despite evidence of harassment and surveillance.

“Rwandans as far-flung as the United States, Canada, and Australia report intense fears of surveillance and retribution.”

—Freedom House, 2021 report.

Activists of Rwandan background in Canada say they have been left out of a federal inquiry into foreign interference, despite evidence that some of them who are vocal against the Rwandan government have been targeted with surveillance and harassment.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) recently arrested one of its members, Constable Eli Ndatuje, and charged him with breach of trust and unauthorised use of a computer. He was allegedly providing information to a foreign government said to be the Republic of Rwanda.

The RCMP cited the arrest, which took place in February, as evidence of foreign interference in Canada. Activists in the Rwandan diaspora say the incident demonstrates how the Rwandan government has routinely spied on its critics in Canada. Rwanda has not officially commented on the allegations.

Testimony

The Canadian Foreign Interference Commission (FIC) has heard testimony by activists from the Chinese, Russian, Iranian, Sikh and Uyghur communities over allegations of intimidation and threats.

But members of the Rwandan diaspora, who have reported similar experiences, say the FIC has not offered them a slot.

“Cases of harassment, intimidation and spying on Rwandan residents or other Canadians who criticise the Kigali regime are well known,” Pierre-Claver Nkinamubanzi, president of the Canadian Rwandan Congress, told The Globe and Mail.

He said he has personally been harassed in e-mails and WhatsApp messages from people using fake names, including one message that threatened him with “big trouble” if he failed to halt his political activities. He also reports that some of his friends have been followed or subjected to attacks.

“I think that the federal government should include Rwanda in its inquiry on foreign interference in Canada,” Mr Nkinamubanzi says.

Paul Kagame, who came to power in the wake of the Tutsi Genocide in 1994, is regularly blasted by his critics and by human rights organisations as a brutal dictator who wouldn’t tolerate any opposition.

To the president of Rwanda, most of the criticism is a distraction from the work that’s required for the country to heal, and to prevent any future genocide. As he did last week on the 30th anniversary of the genocide, he rarely misses an opportunity to remind the world of its inaction, which he says, enabled the massacre.

However, some of Kagame’s critics abroad are dissidents who once worked for his government.

David Himbara, a Rwandan-Canadian economist, and scholar was a one-time advisor to Mr Kagame. He says he suffered threats and intimidation by Rwandan officials after he criticised Kagame’s regime.

He wrote to the Canadian federal inquiry in early February, seeking an opportunity to testify.

“As a Rwandan-Canadian human-rights defender, I have first-hand experience of foreign interference in Canadian affairs,” David told the inquiry in an email.

“My testimony would focus on the government of Rwanda’s interference in Canadian affairs by relentlessly threatening the lives of Rwandan-Canadians who speak out about human-rights abuses in Rwanda.”

His request did not result in a satisfactory outcome. He followed up two months later, and was then told he may be called forth as part of further hearings scheduled for the autumn.

“You can be assured we have taken note of the information you have provided about the Rwandan diaspora,” the inquiry told him in its response.

A spokesperson for the Inquiry provided an explanation for why no Rwandan-Canadians testified so far: The inquiry’s current hearings are focused on evidence of foreign interference in the federal elections of 2019 and 2021.

But, as he added, future work will look more broadly at diaspora experiences with foreign interference in Canada’s democratic institutions and electoral processes.

David Himbara anticipates he will have a lot to share about his personal experiences.

In one incident—as he told the Globe and Mail—some Rwandan media outlets doxed him by publishing his Toronto home address.

And in another, in 2019, a Rwandan defence attaché pleaded with a Rwandan-Canadian friend of Himbara’s to find a way to “silence” him.

The former Kagame adviser took the information to the Toronto police, and got the promise there would be an investigation. In the end, no further action was taken.

All the reported incidents started after Himbara testified to a U.S. congressional committee about the state of human rights in Rwanda, prompting Mr. Kagame to denounce him publicly in a speech.

But criticism of the Rwandan government is not limited to members of the Rwandan diaspora.

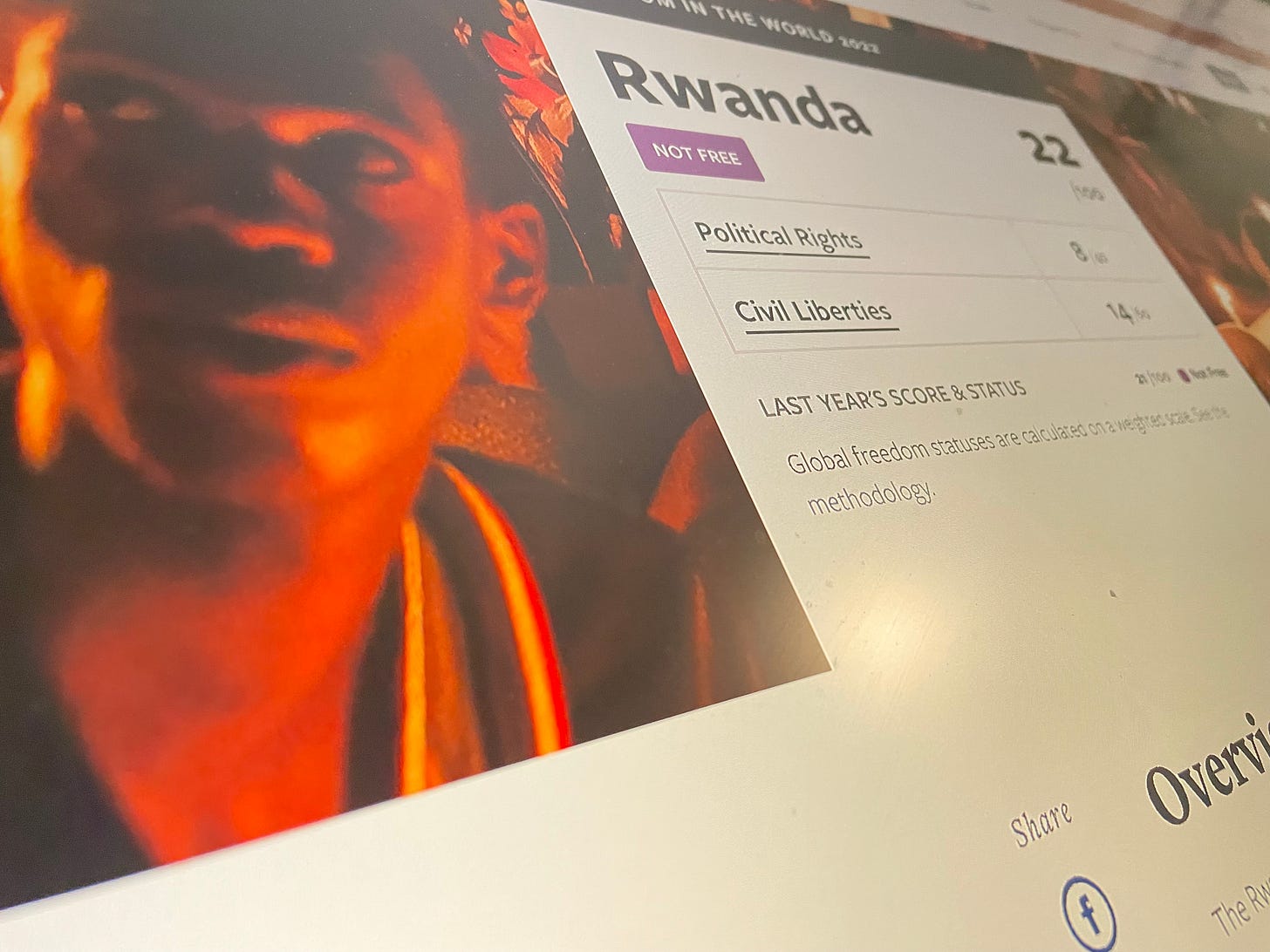

Human-rights groups, including Freedom House and Human Rights Watch, have documented what they present as a campaign waged against real and perceived opponents of the Rwandan government.

These organisations say that dissidents forced into exile have been subjected to killings, kidnappings, enforced disappearances, surveillance, and intimidation.

And some agents involved in these acts of surveillance and intimidation have been open about their assignments after they defected.

In one of the most spectacular cases, South African authorities issued arrest warrants for two Rwandans who allegedly killed a dissident in Johannesburg and fled to Rwanda. Police and prosecutors said the suspects have close links to the Rwandan government.

The incident had put some strain on the relations between South Africa and Rwanda, and the two countries are yet to strike what could be described as entente cordiale.

Beyond the dramatic incidents in South Africa, the plight of Rwandan dissidents at home and abroad—whether attributable to some patriotic lone wolves or to some official entity—appears to be well documented.

“Rwandans as far-flung as the United States, Canada, and Australia report intense fears of surveillance and retribution,” Freedom House said in a 2021 report.

Thirty years after the Genocide—as the country seeks to strengthen nationhood and achieve justice and reconciliation among Rwandans, this seems to be a critical issue that requires attention.