Africa's Best Interest Under Trump 2.0 Lies in America Leaving It Alone

But "The Donald" may yet be the U.S. president whose African policy would turn out to be popular with this generation of Africans—Turning Point Africa.

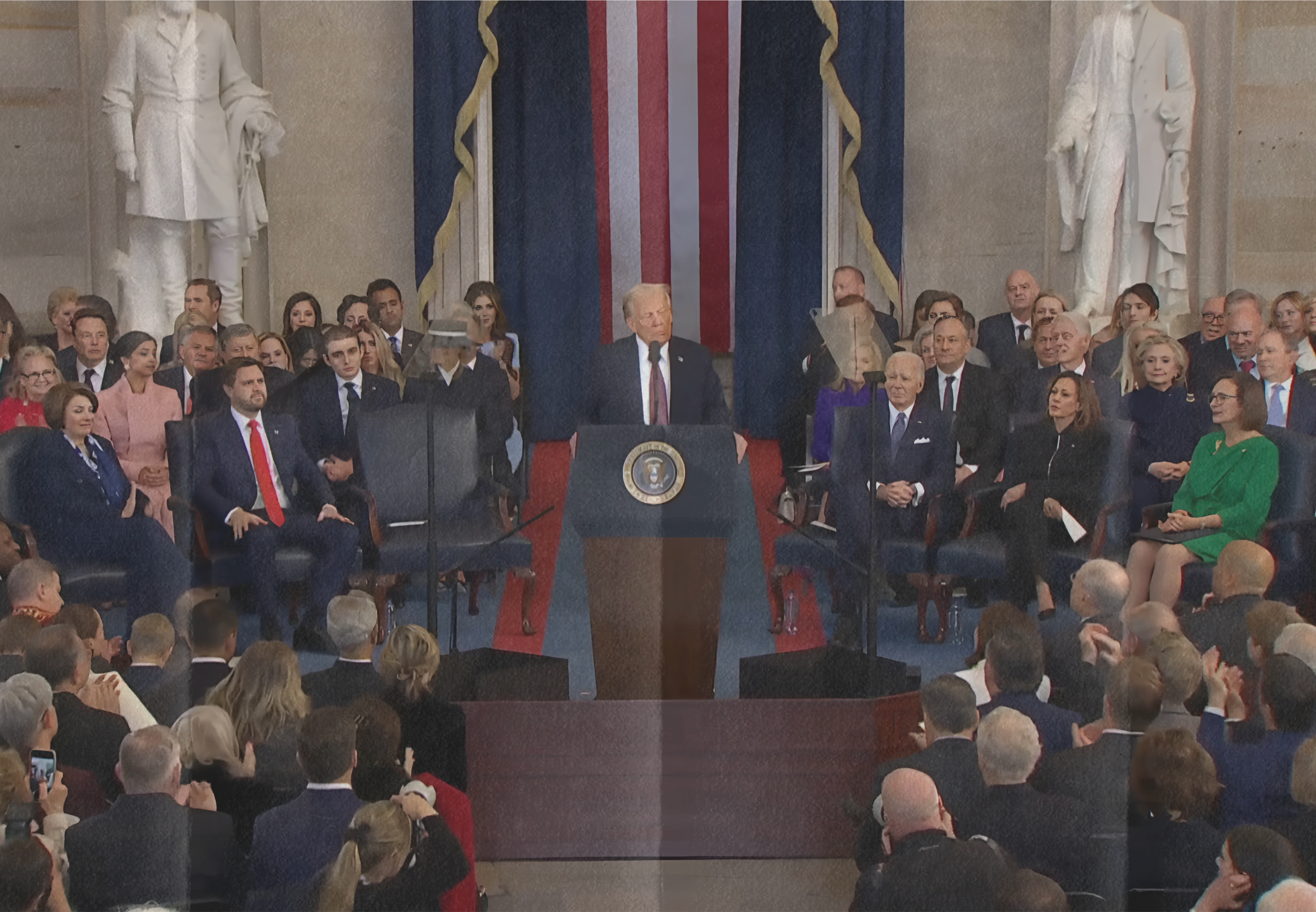

As Donald Trump took the oath of office on Monday to return to the White House, there popped up the traditional question as to what Africa could expect from the new administration. If anything, less direct U.S. intervention could potentially allow more autonomy for African nations to shape their own economic and political futures.

The Straight Talker

Donald J. Trump has a trait that’s uncommon in politicians. He’s a straight talker; he speaks his mind. Sure, he may launch into one of his signature weaves. But when he’s done, he always leaves you with no doubt as to where he stands on the issue at hand.

The professional political entrepreneur who prospers on ambiguity would find him to be frustrating. Because Trump’s candour puts him to shame; it reminds them that they’d dread it if their own thoughts were spoken aloud.

A Nigerian investigative journalist, known for his criticism of the Biden Administration’s foreign policy, sees an advantage in having Donald Trump back at the White House: “Friends and foes do not have to second-guess Uncle Sam; they'd know what he is up to.”

Trump is more signal than noise when it comes to where he wants to take America. Because the man is transparent in that regard, there’s little to no mystery about most of what you can expect from his second term.

From immigration to the key issue of the economy, from global security to the climate, from gender identity to free speech, Trump has laid bare all his plans. And there’s no mystery either on his prospective African policy.

Africa does not feature highly in Trump’s America First agenda. And we know it, rather counterintuitively, because Trump has been as silent on the continent as he’s been effusive on China, on Russia and Ukraine, on Gaza, on Europe and Nato.

What we know is substantially informed by the presidential campaign and by what had been Trump’s approach to Africa when he was first at the White House.

Trump’s previous African Policy had been about “advancing U.S. trade and commercial ties with nations across the [continent] to benefit both the United States and Africa.”

It had also been about security—about “countering the threat from radical Islamic terrorism and violent conflict.” But in the personal book of The Donald—when we last checked—Africa is a collection of “shit-hole countries.”

Granted, his view of the continent might have secretly evolved. But the presidential campaign was marked by distinctive fear-mongering against Haitian immigrants. “They are eating the dogs.” Remember that line?

Now, Haiti had the dubious honour of sharing with Africa that Trumpian expletive portrayal, now infamously part of the record of his previous administration.

With an outstanding pledge of mass deportation of illegal immigrants already on American soil, Trump must view Africa as an inconvenient source of potential influx of candidates for the American Dream.

The businessman may have tried hard, or he just doesn’t bother. For sure, there’s no public update from him to suggest a favourable perception of Africa as a place that fits within his MAGA agenda.

Certainly, with a Department of Government Efficiency, DOGE, designed to slim down public spending, the new administration will not be any eager to channel development assistance to African countries.

Quite predictably still, the traditional question popped up after Trump’s victory was announced on 5th November: What will all of it mean for Africa? A somewhat absurd question.

Donald Trump was elected to serve American interests. What Africa expects of him is utterly irrelevant. Also, it assumes that familiar pessimistic gaze; it assumes that Africa remains a somewhat static continent that awaits to be held by the hand, to be assisted, to be commanded.

Trump 2.0 will inevitably frustrate such a stagnant Africa—an image disconnected from the reality of an ever more dynamic continent. In any event, the slogan out there is America First. There’s no Africa in it.

This might be a better way to frame the issue of the prospective US African policy under the incoming administration: Can the United States—in its battle for global hegemony against China, and against the resurgent Russia—afford to be indifferent to Africa?

A “New Centrality”

The Senegalese-born former official of the French Government, Rama Yade, is right when she argues that much has changed in Africa since Donald Trump left the White House in January 2021.

“African nations have an ace up their sleeve,” Ms Yade writes in a piece for the Atlantic Council. But what’s that ace? Well, it’s what the ex-diplomat calls a “new centrality on the world stage.” It’s the notion that African countries are highly courted partners around the world.

The result is that Africa has options that were unavailable under the solid unilateral world order, the world of Bretton Woods’ dominance led by the U.S.—that world where the BRICS were barely a concept.

If only because of Trump’s stated desire to maintain the US dollar as a trusted global reserve currency, it would be deluded on his part to confine Africa to the same old clichés.

As Apple CEO Tim Cook would know, the business model of Silicon Valley would be unsustainable without Africa and its rare minerals—whether stolen or otherwise. And the point here is that Africa, as a land of vast natural resources, is not a myth.

And with a population projected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050, the continent is a vast market, a last frontier for economic growth—one waiting for a shift of vision: a break away from dependence on foreign aid in favour of more sovereignty, more industrialisation, more trade with its global partners.

That’s a fact every European power has understood since the 17th Century. And Emmanuel Macron of France knows why America under Trump must avoid the amateur mistake of thinking of Africa as little more than a “shit hole.”

Certainly, it’s a fact well understood by China, by the BRICS. And that’s why Africa is centre-stage in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). And do you remember the goal of the BRI?

The so-called New Silk Road is designed to serve Chinese global hegemony, while breaking with the tradition of militarism that’s been so dear to the U.S., known for its thousand army bases worldwide and its foreign military interventions.

Military interventions don’t sell in Africa today. Africans, mainly in the Sahel, will remember for a long time to come the havoc wrought upon their region by Barack Obama’s and Hillary Clinton’s destruction of Libya.

Now, contrary to America’s past use of brutal force to reshape the world according to its interest, the New Silk Road sells a vision of a peaceful and brighter future for all—for China, Asia, Africa and for Europe.

To that end, it pushes for regional connectivity through economic cooperation. Admittedly, some Western analysts see “the project as a disturbing expansion of Chinese power.”

And the U.S., beyond the usual talk of fighting global terrorism, which seems to justify the expansion of its global network of military bases, “has struggled to offer a competing vision.”

Militarism, for sure, isn’t how America will effectively ensure that its dollar remains the world’s currency. It is well and good for hawkish American senators to wax American might.

But for the rest of the world, America has to offer value. And militarism or indifference won’t be how Uncle Sam retains any relevance for Africa, the continent of unbounded resources, the last frontier for economic growth.

And with a future bank of the BRICS, with a future BRICS currency—in other words, with viable competition against the Bretton Woods system and the US dollar—it’s utterly bonkers for any administration in Washington to take Africa for granted.

Like most things about Africa, the notion of the continent as a collection of shit-hole countries—a continent that only contributes illegal migration and diseases to the world—is a colonial stereotype.

A new world order is upon us. If Donald Trump fails to take notice of it, Ms Yade would be right that his America First agenda may take a backseat to an Africa First renaissance—all to the advantage of America’s rivals on the global stage.

So, beyond old-fashioned militarism, beyond stereotypical contempt, what’s the type of US African policy that would make Uncle Sam a relevant player on the world’s last frontier of economic growth—Africa?

Turning Point Africa

There are a few African countries where the leaders are still rather conservative in how they view their relationship to Western powers—one of quiet deference. Ivory Coast, for example. Or even Nigeria—a country whose president is accused of being a CIA asset.

They may criticise the West, but only out of lip service to their impatient populations. In reality, these client heads of State thrive on Western paternalism. And for Conservative Africans, an indifferent United States would be bad news.

It leaves them exposed to possible winds of internal accountability, to the prospect of popular revolts. And Kenya’s budget riots of last year is such a cautionary tale.

Then, there is the other Africa. Turning Point Africa, as you may call it. And you may look to the Sahel to understand the nature of it. In Turning Point Africa, there’s been a progressive awakening of the masses to the failures of imitation.

More than 60 years of independence, under simulacra of democracy, yielded little but despair. The once-tolerated corruption of urban elites turned unbearable when the violence of armed groups came to add up to widespread poverty.

In these countries, globalisation is now a dirty word. Democracy seemed to have only created a marginal peace for the exploitation of Africa’s natural resources by foreign companies that ship out all proceeds, barely paying taxes, mostly paying bribes.

Much like the MAGA crowd that has been instrumental to Trump’s victory, populations in Turning Point Africa want Africa for Africans first. Immigration to Europe or America—where they would be undesirable, scapegoated by far-right political activism—isn’t attractive.

The Sahel’s response to America’s Donald Trump has been the rise to prominence of military leaders in Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso; the election in Senegal of the youngest president ever.

Like Donald Trump and his MAGA base, these are patriots. They want control of their own destinies—more independence, more sovereignty, more freedom to trade with any global partner, under a win-win deal.

They want to be left alone to cherish their local cultures and customs—free from ideological imperialism, free from godless post-modern norms that happen to be fashionable in America or Europe.

Like Donald Trump and his MAGA base, Turning Point Africa—and the whole new Pan-African movement behind it—is vilified. Their rejection of unbridled globalism threatens a world order that has confined Africa to the role of provider of natural resources and passive consumer.

Western critics, media pundits and academics, dismiss them as a “danger to democracy,” even though 40 years of Western-style democracy did little for these impatient Africans.

Then comes Donald Trump with a brand of patriotism that mirrors the aspirations within Turning Point Africa; Trump with his talk of doing more business with the rest of the world, rather than starting or funding wars there. And why does that matter?

“Since China is hellbent on capturing Africa as a business destination,” one professor of international relations told a US news outlet, “Trump will come to Africa not so much because he cares about Africa but because he’s coming to counter Chinese influence on the African soil.”

And as a practical businessman and as a global peace-maker, Trump could only come pushing trade, which would be to Africa’s advantage.

With Trump’s focus on boosting US domestic production as part of his America First agenda, he will need to “import a lot of raw material from all over the world.” If anything, Africa would be there to offer minerals.

Beyond trade, however, Trump’s conservative positions on social issues endear him to Africa. From Senegal to Mali, from Burkina Faso and Niger to Uganda and Ghana, Africans have been impatient with the Democrats’ impulse of exporting certain post-modern values, such as the new LGBTQ+ order.

Nothing makes an African leader more popular than standing up to values viewed locally as disruptive, as colonialist and as antithetical to African traditions. In fact, China has been charming to Africans exactly because Chinese diplomacy does not centre any ambition of substituting African values with their own.

Now, Donald Trump is an avowed “anti-woke” president who advocates a return to more traditional values. And Ms Yade makes a good point when she says, “this would resonate positively” in several African countries where it’s criminal to push any LGBTQ+ agenda.

So, what’s the bottom line here?

Within the grand scheme of global geopolitics, Donald Trump’s personal views on Africa would come to matter less. If only for the sake of taking the competition to China, Trump can’t afford to sneer at Africa, a continent with such obscene reserves of strategic resources.

In any event, less direct U.S. intervention could potentially allow more autonomy for African nations to shape their own economic and political futures. But Donald Trump may yet be the U.S. president whose African policy would turn out to be popular with this generation of Africans—Turning Point Africa.